How often does a problem that defies a solution in waking life get resolved in a dream?

Don’t know about you, but I believe that hard work combined with mastering one’s craft can solve just about any creative problem. Just about… Still, I find there remain certain VERY STUBBORN problems that refuse to be solved the normal way. After “banging my head against the wall” or trying to force a solution, the answer often appears—without effort—the moment I relax! This has happened to me so many times I now believe that the old saying, “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again,” should be revised to say, “If you don’t succeed after try-trying again, TAKE A NAP ALREADY!” When the mind slows down and uncoils, problems naturally untangle themselves.

What accounts for the changes in our brains that give us solutions through dreaming? During the waking hours, our minds are full of high-frequency, low amplitude beta waves – somewhat like thousands of erratic of ripples on water. As we relax, the chaotic beta waves gradually transform in to alpha waves, which are slower frequency, larger amplitude, and more harmonious – similar to ocean waves rolling one after another onto a beach. As relaxation deepens, we enter actual sleep. The mind switches from alpha to theta waves, which are even slower and larger than alphas—more like the huge dip and swell out at sea. From here, new and wonderful wave patterns take us deeper into sleep, and ultimately into a state called REM or Rapid Eye Movement where the most vivid story-like dreaming occurs. It’s as though we close our eyes and fall asleep, and then our “inner eyes” open back up inside the dream-world during REM!

Below, we will look at some examples of three powerful ways dreams help the creative process. First, we’ll see how solutions reveal themselves while drifting off to sleep or slowly coming awake, a state called hypnagogia. Second, the full-blown dream of deep sleep may have irrational content that, on waking, inspires the core creative direction of a work. Third, we’ll see how dreams speak a language unique to the dreamer, redolent with symbols, characters, and bizarre events, capable of solving problems that defy logic and effort. Finally, I’ll give you three techniques you can use to make dreams a vital part of YOUR creativity.

Hypnagogia: preview of the dream world

“Sun is the reason all the happy trees are green

Then who can explain the light in your dreams?”

-Cat Stevens

The state between being awake and falling asleep, called hypnagogia, is a time of visual and auditory hallucination—and inspiration! When falling asleep or slowly waking up, our minds cross a transitional threshold between states of consciousness. Entering the borderland between waking and sleep is a little like watching a movie trailer for the wild and messy world of dreams. Our eyes—and as you will see below, our ears and other sensations—apparently fall asleep before the rest of our mind does, kind of like a foot “going to sleep” while the rest of our muscles stay alert.

Studies show that hypnagogia is particularly helpful for exploring phantom or hallucinatory images while the mind is still capable of critical thought. In other words, while our eyes are metaphorically “open underwater,” already peering into the dream world, our minds are still “on dry land” and semi-awake: they can analyze, reason, and think in a logical way.

Did you know that it is possible to develop your ability to enter and stay in the hypnagogic state? Meditation, when regularly practiced, develops a specialized skill of “freezing” the hypnagogic process in the alpha wave stage, and later in theta waves—the first stage of sleep. This means we can use meditation as a doorway to deliberately open ourselves to creative solutions!

Did you know that it is possible to develop your ability to enter and stay in the hypnagogic state? Meditation, when regularly practiced, develops a specialized skill of “freezing” the hypnagogic process in the alpha wave stage, and later in theta waves—the first stage of sleep. This means we can use meditation as a doorway to deliberately open ourselves to creative solutions!

Here are some of the sensory phenomena that occur during hypnagogia:

- visual “sights” – including random geometric shapes and patterns called phosphenes, as well as other dreamlike hallucinations

- tetris effect – a sensation of movement, often following a new and repetitive task, such as skiing, driving a car, raking leaves, waiting tables, swimming, riding a boat, playing chess, and so forth

- sounds and auditory hallucinations – often fragmented and nonsensical such as hearing one’s own name, a doorbell ringing, random speech, or music!

The author Mary Shelley saw in a hypnogogic state the “creature” which became her most famous character: “Frankenstein.” She describes her mental state, “When I placed my head upon my pillow, I did not sleep, nor could I be said to think … I saw – with shut eyes, but acute mental vision … the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half-vital motion.” What is interesting about Shelley’s account is that her vision was accompanied by intense fright. According to Jungian scholars, fear is the emotion a person often feels when new material ruptures up from the unconscious mind in a dream. Of course, it helps that “Frankenstein” falls within the horror genre!

Perhaps the most famous example of a problem solved during hypnagogia is August Kekulé’s discovery of carbon’s tetravalent (tetra=four) structure. Here, the hallucinated geometric patterns of hypnagogia led to a major scientific breakthrough. “I fell into a reverie, and lo, the atoms were gamboling before my eyes! … up to that time, I had never been able to discern the nature of their motion … the whole kept whirling in a giddy dance … I spent part of the night in putting on paper at least sketches of these dream forms. This was the origin of the Structural Theory.”

Apparently Kekulé, so impressed by the dreamlike state that he started exercising his “mental eye,” was rewarded with a second major scientific discovery. Dozing off by the fire, he “saw” abstract geometric shapes, which he perceived as atoms. Kekulé notes that he could now discern larger, more complex structures, one of which appeared to be a snake seizing its own tail (creating a circle). He woke and excitedly spent the rest of the night working out his circular hypothesis for the structure of the Benzene molecule.

Irrational Insights

I am enough of an artist to draw freely upon my imagination. Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.

-Albert Einstein

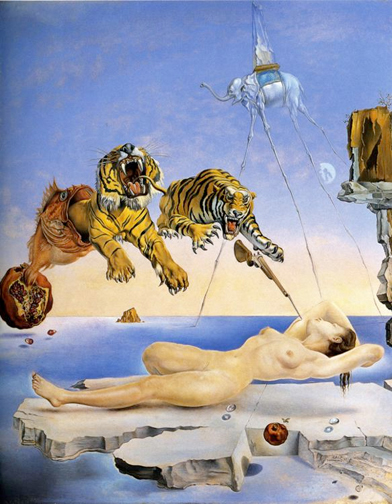

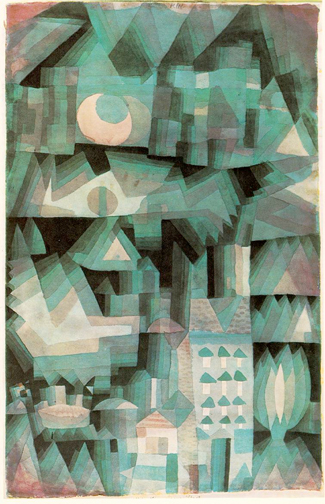

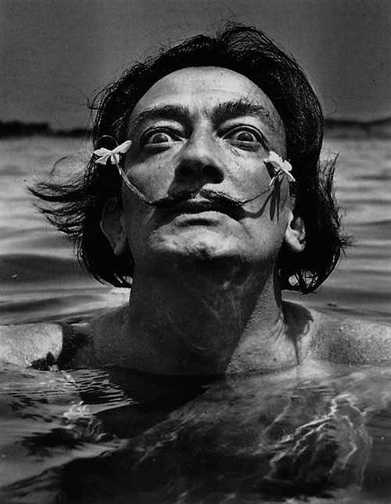

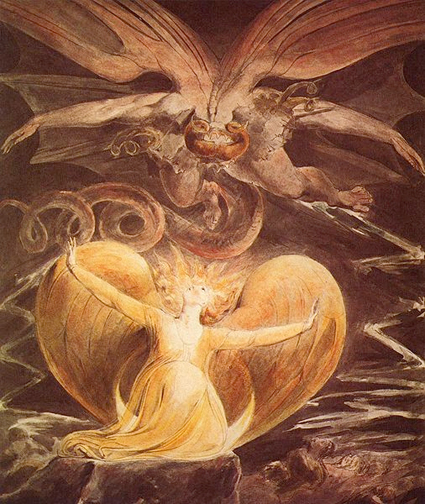

Not all problems can be solved with effort, logic, and normal rational approaches. Beyond the chimera of the hypnagogic state we enter the deeper realm of nighttime dreaming. Dreams can be perplexingly difficult to analyze or make hard rules about, yet they are full of the raw material of visualization, creativity, and inspiration. The tendency of dreams to be more intense or “real” than reality makes them one of the greatest tools for inspiring creativity. The artists, mathematicians, and inventors below used actual dream content for their creative daytime work.

Two powerful examples of musical inspiration come from dreams. Richard Wagner’s opera “Tristan and Isolde,” highly regarded in musical history for its unusual orchestral coloring and harmony, came to him entirely in a hypnogogic state. The tragic story involves a prophetic curse, poison drinks and deaths, and lovers meeting only in the lightless world of night. “For once you are going to hear a dream. I dreamed all this [“Tristan”]. Never could my poor head have invented such a thing purposely.”

Similarly, Paul McCartney woke one morning hearing a lovely tune in his head. He got up, sat at the piano, and found the note G. By listening to the echoes of a dream-tune, he followed the pattern of notes to F sharp minor, to B and E minor and then back to E. This progression struck McCartney as logical. Yet, because he had dreamed the tune, he couldn’t believe he’d written it—the experience struck him as magical! The tune was Yesterday, among the most well known and well loved of all the Beatles’ songs.

One of the most brilliant mathematical geniuses in history was similarly inspired by his dreams. His genius was so great we might speculate that he dwelt much of the time in a dreamlike state of awareness. Srinivasa Ramanujan was from a good but poor family in India, whose family deity was the Hindu goddess Sri Namagiri Lakshmi. Ramanujan often dreamed of the goddess.

“While asleep I had an unusual experience. There was a red screen formed by flowing blood as it were. I was observing it. Suddenly a hand began to write on the screen. I became all attention. That hand wrote a number of results in elliptic integrals. They stuck to my mind. As soon as I woke up, I committed them to writing.” Ramanujan verified the formulae presented in his dreams. His work is regarded as original and highly unconventional, and has inspired a vast amount of additional research including applications in crystallography and string theory. “An equation for me has no meaning, unless it represents a thought of God.”

Dream language

Beyond providing the raw content of creative work, dreams can offer the solution to a particular problem through bizarre images and events. The language of dreams is highly personalized and symbolic, with evolving grammar and syntax peculiar to the dreamer. Jungians believe that dreams are a product of “dissociated imagination,” a chimerical mental function disconnected from the conscious self. Visions, sounds, and images from our sensory memory are the elements of the dream language.

The story of Elias Howe, who invented the sewing machine, is a striking example of the strange and powerful language of dreams. Howe’s dream came in the form of a nightmare, of which two versions exist. The first has him in a pot of boiling water with cannibals dancing around him, whose spears have holes in their tips—an image which struck him on waking. A second version features Red Indians who shoot arrows through a cloth wigwam and snag threads, which they are able to pull through to the other side (similar to the problem of the sewing machine). Either way, Howe dreamed of the hole in the “wrong” (illogical!) end of a needle: namely, at the point or tip, instead of the head where the needle’s eye usually is. This irrational vision solved the problem of mechanizing a lock stitch from two threads.

Finally, horror novelist Stephen King uses his nightmares as a source for solving story problems. The inspiration for Misery arose from a dream on an airplane. “I’ve always used dreams the way you’d use mirrors to look at something you couldn’t see head-on, the way that you use a mirror to look at your hair in the back. To me that’s what dreams are supposed to do. I think that dreams are a way that people’s minds illustrate the nature of their problems. Or maybe even illustrate the answers to their problems in symbolic language.”

How to Work with Dreams Creatively

Here are some suggestions to help you start using—or go to the next level with—your dream processes:

- Keep a Dream Journal.

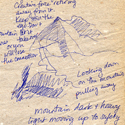

Jot down everything you remember as soon as you wake up. Don’t think, narrate, or edit. Try to write down the images, feelings, words, places, and characters that appear in dreams. After a while, you will notice recurring patterns that relate to your life situation, psychological state, and even your creative projects!

Jot down everything you remember as soon as you wake up. Don’t think, narrate, or edit. Try to write down the images, feelings, words, places, and characters that appear in dreams. After a while, you will notice recurring patterns that relate to your life situation, psychological state, and even your creative projects! - Set a Conscious Intention Before Sleep. Ask for the answer to a problem to be revealed to you in a dream. Open your heart and let the dream world’s special messages in. Whatever comes, don’t question it but write it down and see how its meaning unfolds over the course of time.

- Practice Meditation. Set aside time every day to sit quietly. Close your eyes. Focus on your breath. Slow down your breath. Let each inhale and exhale be slow and deep, alternately filling and emptying your lungs. Yogi Bhajan said, “The mind follows the breath.” Let the breath become quiet and the mind will also quiet down. Meditate on your breath. Be open to whatever images and thought-fragments flow past, releasing them as though into a stream and remaining focused on the breath.

For that VERY STUBBORN problem on your plate today, I hope you will invite the dream world into your life. Tonight, or the next time you cross the hypnagogic threshold—while your eyes are already dreaming yet your mind is still awake—perhaps the solution will reveal itself to you. Possibly during REM sleep the mysterious symbols of dream will communicate what your subconscious mind has already figured out. Maybe you will practice meditation with the goal of floating on brainwave currents until the universe “speaks” to you. Whichever approach you take, may the magical inspiration of dream states be yours!

©2011, Sonya Shannon. All rights reserved.

Sources:

Paul McCartney — Many Years From Now, Barry Miles (NY, Henry Holt, 1997)

The Committee of Sleep, D. Barrett, 2001

Deirdre Barrett, a Harvard psychologist, 2001 study

James H. Austin, in his book Zen and the Brain

Ramanujan, the Man and the Mathematician, S. R. Ranganathan, 1967

Interview with Stan Nicholls, SFX Magazine no 45; December 1998

Writers Dreaming : 26 Writers Talk About Their Dreams and the Creative Process , Naomi Epel, 1994

The Committee of Sleep , D. Barrett, 2001

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Srinivasa_Ramanujan

Comments on this entry are closed.

Sonya, this article is deep, and worthy of considerable perusal. It may help to explain why some of us creative types produce the work we do. There is so much to learn about the human brain and how it functions, particularly when it is supposedly asleep – but then, is it ever?

Very good piece, Sonya. I’m always fascinated by the dream state, and enjoyed your examples of people who have found solutions within their dreams. I dream every night and remember them most of the time. As an artist I don’t usually like to try to control my dreams, and haven’t used them to try to solve a problem, but I’d like to give it a try. I keep a dream journal, and have sometimes used this to inspire a painting or a poem.

Thank you for your research and work on this fascinating subject.

What a ‘dreamy’ post! Thanks for the vivid explanations, accounts and inspiring tips. Your beautifully written post and a lesson learned from one of my recent dreams have given me a great idea for a post on my own blog. Thanks for sharing.